Tēnā koe te Kaiwhakahaere ko Tom. E te whānau kākāriki, tēnā tātou. Ko Grant Brookes tōku ingoa. He mema o te uniana ahau.

Greetings everyone. Thanks to Rongotai Branch Co-Convenor Tom, for inviting me to speak. My name is Grant Brookes. I’m a trade unionist. As mentioned in Tom’s introduction, I am also the National Co-Convenor of the PSA Eco Network, although I should stress at the outset that I am not speaking on behalf of the PSA this evening.

My topic for tonight, on the eve of the 2021 School Strike 4 Climate, is the relationship between trade unionists and environmentalism, and what this means for Green Party members. These notes will go online, where there will be lots of links to sources and to more information. I’ve been given half an hour for this talk.

I would like to begin with a story – one which featured in an article in Forest & Bird magazine in February 2010. “During the 1970s and 1980s, Whirinaki [on the edge of Te Urewera] became a battleground as conservationists fought to protect New Zealand’s finest remaining giant podocarp forest from Forest Service logging.”

Eventually, “after the Labour Party won the 1984 election, selective logging at Whirinaki ended, and later that year Whirinaki Forest Park was born” – but not before a confrontation had taken place at the small mill town of Minginui, in June 1978. Here is a photo from that day, reprinted in Forest & Bird.

Local timber workers and iwi members are blocking the road against environmentalists from the Native Forest Action Council (NFAC). They hold a banner for an opposing “NFAC”, a “National Front Against Conservationists”. A placard on the right of the photo says, “People Before Birds – Jobs Before Parks”.

Unions vs. the environment

There’s no getting around it. Such sentiments of working people have sometimes been taken up and amplified by unions.

On 4 May 2000, for instance, the Greymouth Evening Star carried an interview with Jim Jones, Wood Sector Secretary of the National Distribution Union. Two years earlier, the Timberlands State-Owned Enterprise had announced plans to triple the felling of native beech on the West Coast. This sparked a concerted campaign by environmentalists in the Native Forest Action group.

The National Distribution Union told the Greymouth Evening Star that the green movement was guilty of “emotive bullshit” and that logging of Crown-owned native timber should be allowed. The Furniture Association had claimed that without native logging, 4,000 jobs could be lost. “I have a saying”, said Jones, “that you have to be on the planet before you can save it.”

Of course, it isn’t just in forestry where trade unionists and environmentalists have clashed. As recently as 2017, E Tū union praised Australian conglomerate Bathurst Resources and Talley’s Fisheries for a plan to expand coal production at the Stockton Mine by 50 percent. The argument was same: “More coal would mean more jobs”, E Tū union organiser Garth Elliott told the Otago Daily Times. There are other, similar examples.

‘Unity between struggles’

But right from the birth of the modern environmental movement in the 1970s, there have also been examples of trade unionists and environmentalists working hand in hand. One of the most internationally significant cases is the New South Wales Builders Labourers Federation (BLF). In the early Seventies, this union pioneered the use of industrial action to protect the natural and built environment of Sydney.

The first of their famous “green bans” was in support of a campaign led by a group of women on Sydney’s North Shore to save a piece of undeveloped land called Kelly’s Bush. When approached for support in June 1971, the union suggested that the women call a public meeting. Attended by 600 residents, the meeting formally asked the BLF to prevent construction on the site. The developer retaliated by announcing that they would use non-union labour as strikebreakers. In response, BLF members on the developer’s other construction projects downed tools. The developer backed down and Kelly’s Bush was saved.

The alliance between trade unionists and environmentalists at Kelly’s Bush captured the imagination of environmentalists, residents and heritage campaigners and soon spurred other successful campaigns. Between 1971 and 1974, 54 of these green bans were imposed across NSW. Bans were extended to express solidarity with the right of women to work in the building industry on equal pay, to support anti-motorways campaigns and for Aboriginal justice. In 1973, the BLF imposed a “pink ban” when Macquarie University discriminated against a gay student.

In a letter to the Sydney Morning Herald in 1972, Jack Mundey (NSW BLF Secretary 1968-1975) explained the thinking behind these bans. He challenged the idea that jobs must always come before the environment: “Though we want all our members employed”, said Mundey, “we will not just become robots directed by developer-builders who value the dollar at the expense of the environment. More and more, we are going to determine which buildings we will build… The environmental interests of three million people [in Sydney] are at stake and cannot be left to developers and building employers whose main concern is making profit.”

Jack Mundey passed away in May last year, aged 90. In a statement from NSW Greens, party Co-convenors Sylvia Hale and Rochelle Flood said: “Under his leadership of the Builders Labourers Federation, for the first time we saw unity between the struggles of unions and environmentalists.

“The Green Bans born out of this unity reshaped Australian politics and delivered significant wins for heritage, urban bushland and public housing. The union stood shoulder to shoulder with the community in fighting developments whose sole purpose was to enrich the few at the expense of the many.”

But even before the first green ban was imposed across the Tasman, linkages were already being forged between trade unionists and the emerging environmental movement here in Aotearoa.

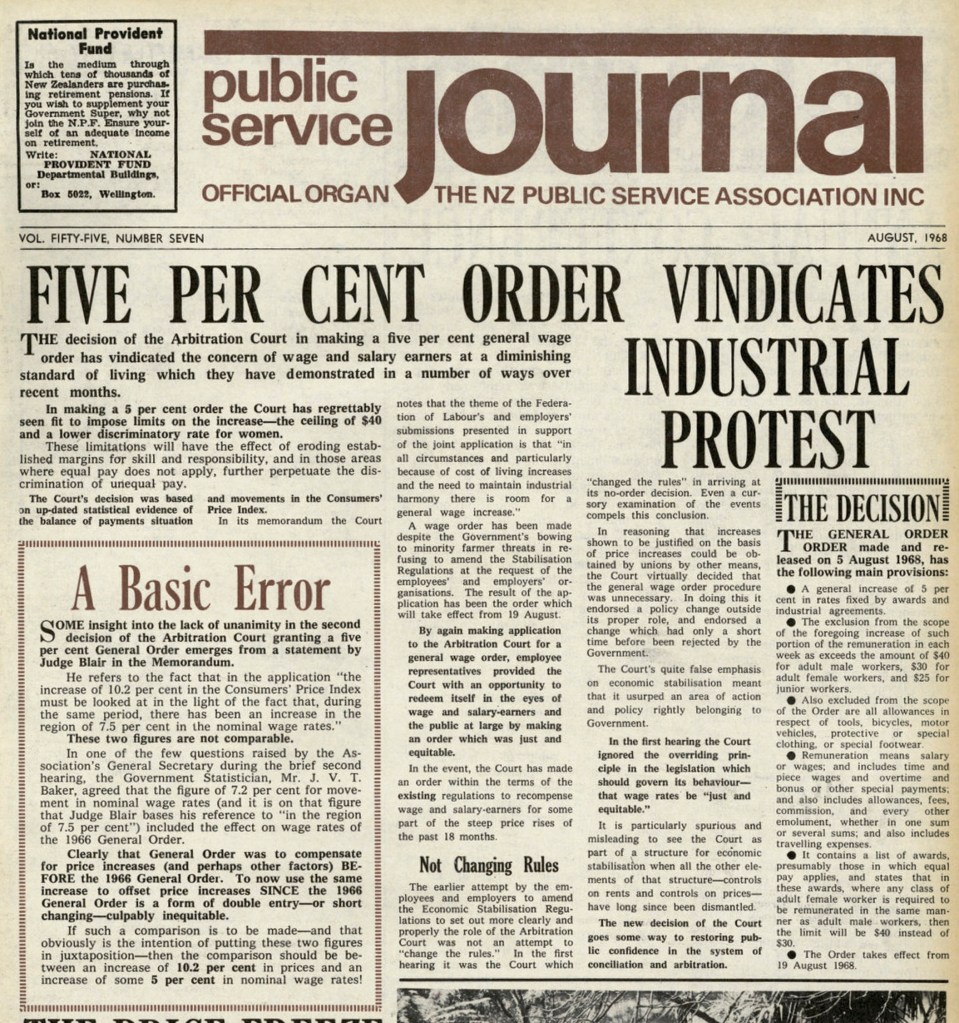

This is a page from the December 1970 issue of the New Zealand Public Service Journal. You can see, alongside the ever-popular PSA crossword and an advert for houses in Wellington for a $2,000 deposit, the lead article, titled “Saving Lake Manapouri”.

The “Save Manapouri” campaign marked the birth of the modern environmental movement in New Zealand. Kicking off in 1969, it was our first nationally-coordinated environmental campaign, and the first to influence politics at a national level. In 1970, almost 10 percent of the population signed the Save Manapouri petition. Two years later, it added impetus to the formation of Green Party precursor, the Values Party.

The goal of the “Save Manapouri” campaign was simple. It aimed prevent the construction of a dam which would raise the lake level and drown 800 hectares of forest, all so that “maximum exploitation of the resource” could deliver more cheap electricity to the Australian-owned aluminium smelter being built at Tiwai Point.

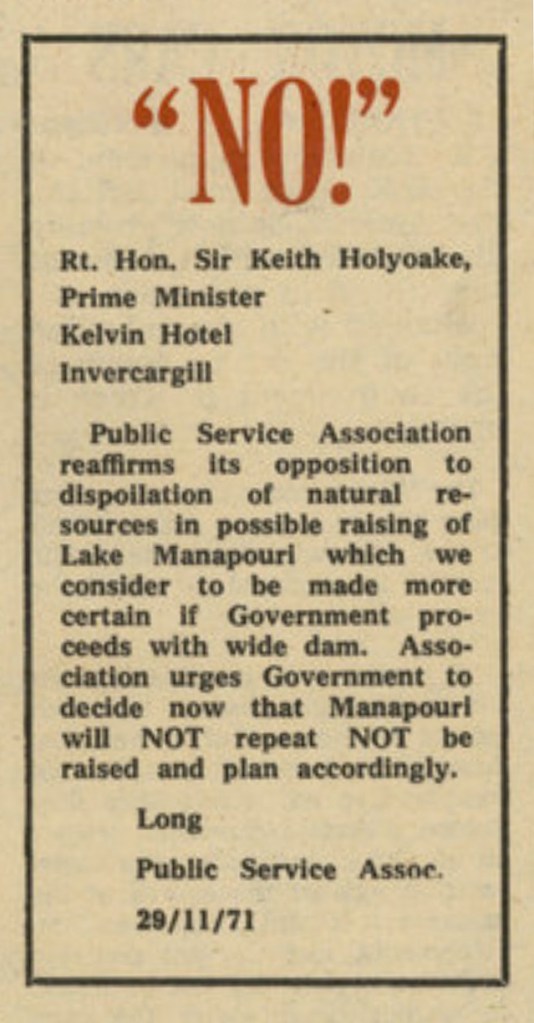

Staff of the Electricity Department at Manapouri belonged to the PSA union. In March 1970, the PSA executive voted to support the Save Manapouri campaign. To drive home the point, PSA National Secretary Dan Long wrote to Prime Minister Keith Holyoake the following year. His telegram, reprinted in the union journal, said:

“Public Service Association reaffirms its opposition to dispoilation [sic.] of natural resources in possible raising of Lake Manapouri which we consider to be made more certain if Government proceeds with wide dam. Association urges Government to decide now that Manapouri will NOT repeat NOT be raised and plan accordingly.”

Why unions matter

It’s now almost 50 years since these events in Australia and New Zealand. Why does this history still matter?

There are a number of reasons. Firstly, it is hard to overstate the enduring international legacy of the green bans movement in NSW. In 1978, the actions of the NSW BLF inspired the Auckland Trades Council to impose a green ban at Takaparawhā (Bastion Point). As Council of Trade Unions Vice-President Māori Syd Keepa has explained, “The reason Takaparawhā (Bastion Point) remained undeveloped for so long was because union members put a green ban on the site, that means they wouldn’t work on the site as long as Ngāti Whātua opposed it.” This helped to ensure the eventual return of land to Ngāti Whātua in 1988, kicking off the historic Treaty settlements process.

It’s even possible that without the NSW example, the Green Party of Aotearoa New Zealand would not exist – at least, not under its current name. Australian Greens leader Bob Brown said, in a speech to the Australian Senate in 1997, that the use of the term “Green” as a political category originated with the NSW BLF. German eco-activist Petra Kelly visited Sydney in 1977, he explained, and was so impressed with the linkage between trade unionists and environmentalism that she adopted the terminology when she co-founded the world’s first Green Party back home, two years later.

But if such a thing can be imagined, there are even more fundamental reasons why these examples are still relevant. Through their green bans, the BLF revealed the rarely-acknowledged economic role of working people. “We are going to determine which buildings we will build”, said Mundey – and ultimately, through our free choice or under some degree of compulsion, the same thing is true for every enterprise, in every area of the economy. In the words of the old union song, Solidarity Forever, “without our brain and muscle, not a single wheel can turn”.

When the Chair of the Climate Change Commission says in 2021 that to create a zero carbon economy, “we need to change how we get around, and rethink what we produce and how we produce it”, what he means is that working people will need to do things differently. And when the Commission’s Draft Advice to Government talks about an “equitable transition” which protects livelihoods and where benefits of climate action are shared across society, and do not fall unfairly on certain groups or people, then what is required is for working people to have a say in how their work is to change.

In other words, the 1970s show us why there can be no equitable transition to a zero carbon economy in Aotearoa without the involvement of unions.

Unionists and environmentalism today

Yet in some ways, times have changed since the 1970s. Wood Sector unionists, now part of First Union, no longer promote native logging. Instead, they call for job creation in “replanting and planting native forests”. Ngāti Whare have apologised for their role in the protest at Minginui. “We realise now that for a period our economic survival instincts caused us to lose touch with our traditional values”, they said – a salutary reminder that iwi, like trade unions, are not immune from capitalist mindsets.

So here in 2021, I would like to highlight three of the most exciting examples of unity between unions and environmentalists today.

The first is the work of New Zealand’s largest private sector union, E Tū, in creating a Just Transition in Taranaki.

Created through a 2015 merger between the Engineering, Printing and Manufacturing Union, the Service and Food Workers Union and the Flight Attendants and Related Services Union, it represents a very diverse group of workers. They include some in the most carbon-intensive sectors of the economy. “Our members work in mining, gas exploration and production, steel and aluminium making, electricity generation and aviation”, says the union. “Many other members work in engineering and services supporting these operations. E tū members in the West-Coast and Huntly mining operations [including Stockton Mine, mentioned earlier], at NZ Aluminium and NZ Steel, Marsden Point and in the on and off-shore Taranaki oil fields support their local community economies with wages and conditions included in good union employment agreements.”

In 2018, after a period of intense internal discussion, E tū issued a public statement supporting a Just Transition to a carbon-free future by 2050. This was followed by a comprehensive Just Transition policy the following year. In some respects, these moves represented a harmonising of national union policy with groundbreaking work already being undertaken by E tū in Taranaki.

A series of decisions made during the last term of Government – including the ending of new offshore oil and gas exploration permits – made it clear that Taranaki’s primary industry will close. Rather than defend fossil fuels, E tū threw itself into the work of creating what comes next:

“E tū believes NZ should lead the way with a strategy of ‘Just-Transition’ in which we start planning now for the transition away from a carbon-based economy while ensuring that working people and their communities do not bear the brunt of this structural adjustment. E tū is part of an international union movement, led by the peak global union organisation ITUC, that advocates for meaningful public and private sector strategies to ensure that good jobs and employment and income-related support is available as we transition out of carbon-linked jobs.

“We call that a ‘Just Transition’ into new employment opportunities, and the work must start now on what is needed in such a Just Transition strategy. We can’t wait until it’s too late. We are not interested in some plan that puts a couple more case officers in regional WINZ offices. We need a strategy for new high-value jobs and other forms of support that are real, practical, relevant, resourced and sustainable.”

And this – called the Taranaki 2050 Roadmap – is what they’ve helped to create.

Having pioneered the work in Taranaki, E Tū is now gearing up for a Just Transition to manage the closure of the Tiwai Point aluminium smelter.

A second contemporary example of unity between unions and environmentalists comes from the education union, NZEI Te Riu Roa. Last year, NZEI became the first union in New Zealand to create a Community Organiser role, focused on climate action. One major piece of work for this new role will be organising with local communities to switch out coal boilers still used in about 200 schools. Some of this new work is documented on video and in media reports.

The final exciting example of trade unionists working hand in hand with environmentalists comes from the public sector, and New Zealand’s largest union. It’s one I’m privileged to be involved in myself.

The PSA Eco Network (formerly PSA Eco Reps Network) was first established by members in 2010 following the development of the PSA Sustainability Policy and Action Plan. The overall purpose of the PSA Eco Network is to build union organisation to improve workplace sustainability and contribute to the global campaign for environmental justice and action on climate change.

Delegates at the 2020 PSA Biennial Congress in November voted to formalise the Eco Network, so we now have official standing within the PSA membership structures. This vote reflected a wider democratic sentiment in the union. We have long known that climate change and other environmental issues are of concern to PSA members, but the 2019 election survey of PSA members highlighted just how important these issues are. Members ranked climate change in their top three issues in election year, after “health and housing” and “families and people”, and above “pay, work and cost of living”.

So far this year, our work within the union has included a contribution to the PSA submission to the Climate Change Commission and advocacy for Climate Justice to be added in the refresh of the PSA Strategic Goals. Our members were also involved in the PSA submission on the Water Services Bill. Externally, many of us are active in sustainability initiatives in the workplace, including the changes needed to meet the Government’s target of a carbon neutral public sector by 2025.

On Friday, we will be marching with the students on their 2021 School Strike 4 Climate.

What can Green Party members do?

What then can Green Party members do? First and foremost, join your union. I’m sure I don’t need to explain why. If you’re not sure which union to join, the Council of Trade Unions has a helpful online tool at union.org.nz/find-your-union/.

But the examples of the 1970s also contain three vital lessons for what else you can do to forge unity in struggle in today. These lessons could equally be demonstrated using the three contemporary examples from E tū, NZEI and the PSA cited just now, but it’s probably safer to refer to individuals and events which are a bit more distant.

Firstly, the 1970s shows the importance of political leadership. Leadership in a union does not equate to having some official title or high-up position. In fact, as Senator Bernie Sanders likes to say, “real change never comes from the top on down, but always from the bottom on up”. Any union member can be a leader – at their workplace, in a meeting or even in an email.

Jack Mundey was a builder’s labourer and a rank-and-file member before he became NSW State Secretary of the union in 1968. Crucially, what he brought to the BLF was political leadership – learnt after joining the Communist Party in his twenties and later demonstrated through his many roles in the Australian Greens. This political leadership also brought the union in behind other movements to end the Vietnam War, to support the Gurindji people battling for justice in the Northern Territory and to stop the 1971 Springbok Tour of Australia. Two NSW BLF leaders were even arrested for breaking into the SCG and trying to chop down the goal posts in a bid to stop the Springbok match from going ahead.

The green bans in Sydney came to an end in 1975, because of a change in union leadership. Jack Mundey and other elected leaders of the NSW BLF were ousted by the union’s national office. Conservative officials were installed to replace them, who did not support union action for the environment. (Astute observers of recent union events in New Zealand might see some parallels). The Federal Secretary of the union who orchestrated this anti-democratic coup was later convicted on 17 charges of corrupt dealings with developers.

The importance of political leadership was also shown in the PSA. The biography of PSA National Secretary Dan Long is pointedly titled, “White Collar Radical”. It documents how the union leadership of Long and his allies, including their ardent support for the Save Manapouri campaign, was guided by their radical politics. In 1970, shortly after the PSA executive voted to support the “Save Manapouri” campaign, National Party Finance Minister (later Prime Minister) Robert Muldoon underscored this point in a speech where he attacked the PSA as, “the most leftist of the State Services unions”. The political leadership in the PSA also saw the union mount campaigns against nuclear testing, apartheid South Africa and anti-Māori racism, which were highly controversial at the time.

So to reiterate – the first lesson of the union-environmental alliances of the Seventies is that political leadership counts. After joining your union, the very next thing that a Green Party member can do is to get involved in leading it.

The second lesson is that if green union leaders want their union to defend the environment, they must also fight like hell for the economic interests of the membership. (The obverse is also true, by the way. Unions that don’t campaign for the environment tend to accommodate poor working conditions for their members).

Sydney in the 1960s was in the grip of a construction boom of “Wild West” proportions. Money poured into new buildings, but wages stayed low. Health and safety on the job, by today’s standards, was virtually non-existent. Between 1968 and 1971, there were more than 61,000 injury compensation cases — some fatal, others creating permanent disabilities — in NSW’s building, construction and maintenance sector. But in May 1970, under new Secretary Jack Mundey, the union started to turn the tide. It organised a five week strike in support of wage increases as well as industrial recognition of the labourers’ skills. The strike ended in victory.

“If it wasn’t for that civilising of the building industry in the campaigns of 1970 and 1971”, Mundey later said, “well then I’m sure we wouldn’t have had the luxury of the membership going along with us in what was considered by some as ‘avant-garde’, ‘way-out’ actions of supporting mainly middle-class people in environmental actions. I think that gave us the mandate to allow us to go into uncharted waters.”

Again, the lesson is the same with the PSA. “In March 1968”, said his biographer, “Dan Long stood before the [arbitration] court and argued that a 13 percent general wage increase was necessary… The court’s decision, issued the following month, was for a nil increase… The response of the union movement was volcanic.” The executive’s decision to throw the PSA’s weight behind saving Manapouri in 1970 came off the back of union support for the “tsunami of strikes” that overturned the 1968 Arbitration Court ruling and delivered a general wage increase.

The final lesson from the 1970s for greens in the union movement is that environmentalism and union democracy go hand in hand.

The first order of business for Jack Mundey and his allies, on taking up the official leadership of the NSW BLF in 1968, was to reform the undemocratic (and often corrupt) structures of union decision-making.

They developed a “a new concept of unionism”. Union executive meetings were opened up to all members to attend. Mass stop-work meetings became the primary forums for deciding union policy. All decisions on green bans and actions, for example, were put to meetings of the BLF membership for a democratic vote. Further, the salaries of union officials were tied to pay rates they negotiated for their union members. Perhaps the most startling innovation of all was term limits for all union positions. To prevent the union from being captured again by corrupt career bureaucrats, it was decided that the officials should come from the job and, after six years at the most, return to the job.

Long-serving Greens Senator and NSW MP Lee Rhiannon has highlighted that, “Rebuilding the BLF as a democratic, members run union could be described as Jack’s first achievement. It was certainly one that laid the basis for the Green Bans movement and the social movement unionism that came to characterise the BLF.”

In this area, it cannot be said that the PSA went quite that far. But earlier democratic reforms by an insurgent left-wing PSA leadership had, the words of Dan Long’s biographer, transformed the PSA from a “complacent and top-heavy guild of senior bureaucrats into a broadly representative and far more effective organisation”. In reporting the PSA executive’s vote to support the Save Manapouri campaign, the Public Service Journal emphasised that it was a reflection of the democratic will of the membership: “This decision followed the expression of widespread concern in Section Committees around the country at the likely effects of the Electricity Department’s proposals.”

Conclusion

In conclusion, three things go hand in hand. Since the 1970s, fighting unions which are member-driven, with green and left wing leadership at all levels (and especially from below), have taken up environmental causes.

The Green Party Charter says that, “ecological sustainability is paramount”. Since working people are the ones who ultimately produce all that is consumed, any shift towards an ecologically sustainable economy will involve us. Any such shift will mean changes in what we do, and how we do it.

Because Greens also believe in a world where “decisions will be made directly at the appropriate level by those affected”, the shift to ecological sustainability must also involve us, and the organisations – the unions – through which we participate in economic decisions about our work.

The rationale for unity between trade unionists and environmentalism is surely clear. I hope that this talk has clarified, at least to some small extent, how Greens can help make it happen.

7 April, 2021.